Scientists from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research (ITP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have discovered that it is the increased precipitation rather than warming that has driven the changes of spring and autumn phenology in alpine grasslands at high elevations like the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet) Plateau.

Investigating the background of warming and humidification across the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, researches have provided important scientific support for scientists to correctly understand the response mechanism of the alpine grassland ecosystem to climate change, according to a CAS statement sent to the Global Times on Monday.

Luo Tianxiang, a researcher from the ITP, led his team to conduct a two-year field experiment which used infrared warming (ambient, +2C) and precipitation increase for each of rainfall events (ambient, +15 percent, +30 percent) during the growing season in a part of the Tibetan alpine grassland.

Spring green-up dates (GUD) and autumn senescence dates (SD) of three dominant species - naming Stipa purpurea, Kobresia macrantha and Potentilla saundersiana - and the relevant soil temperature and moisture were observed during the research that was conducted in 2013-14. Rainy season onset as well as Pre-GUD or Pre-SD (30 days before GUD or SD) mean air-temperature (T-30d) and precipitation (P-30d) and relevant soil temperature (ST-30d) and moisture (SM-30d) were calculated for each experimental treatment.

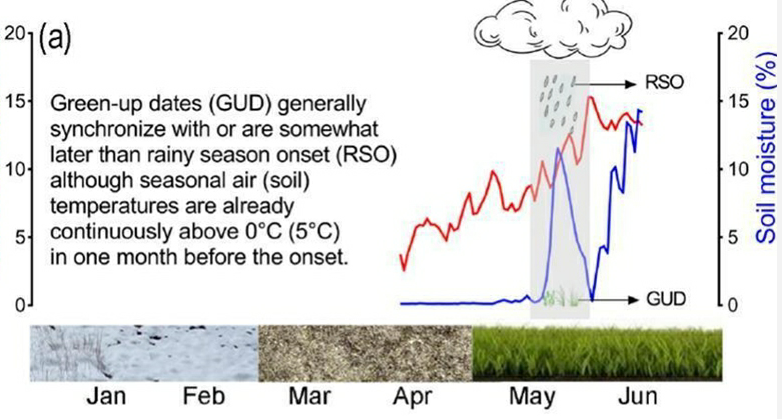

The research found that GUD dates of the three dominant species had advanced by increased precipitation rather than by warming, which showed a robust positive correlation with the onset of the rainy season, according to Ma Pengfei, the first author of a paper on the research released in early February in the Science of The Total Environment.

SD dates were independently delayed by both increases of temperature and precipitation. There was no interactive effect of warming and increased precipitation on GUD and SD across species and years, according to the research.

In general, GUD had a significant negative correlation with Pre-GUD P-30d (SM-30d) but not with Pre-GUD T-30d (ST-30d), while SD showed a significant positive correlation with Pre-SD T-30d and P-30d or Pre-SD ST-30d and SM-30d. The data collected during the research support the hypothesis, indicating that spring and autumn phenology of monsoon-adapted alpine vegetation are more sensitive to precipitation change than to warming. The prolonged growing season length under increased temperature and precipitation is more depended on the delay of autumn senescence than the advance of spring green-up, the paper concluded.

The Qinghai-Xizang Plateau is home to the world's highest and largest alpine meadows and grasslands, whose formation and distribution are mainly controlled by the Indian monsoon climate. How the widely distributed dominant species on the plateau adapt to the cold and arid climate environment at the same time is the key to understanding the phenology response of alpine grassland vegetation to climate change, Luo was quoted as saying in the statement sent to the Global Times.

Over the past 30 years, the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau has experienced rapid warming, accompanied by an increase in precipitation. It is estimated that, by the end of the 21st century, the annual average temperature of the plateau will increase by 2.8-4.9 C, and annual precipitation will increase by 15-21 percent, according to Luo.

Given this, it is debatable whether warming or increased precipitation is the primary reason driving the changes to spring and autumn phenology in alpine grasslands at high elevations like the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. Previous warming experiments rarely paid attention to the impact of precipitation changes, and there were few cases of dual-factor control experiments that combined temperature and precipitation changes, Luo noted.