A multidisciplinary study led by researchers from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Yunnan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology has uncovered the first definitive evidence of Middle Paleolithic Quina technology in East Asia. The findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), are based on artifacts excavated from the Longtan site in Heqing County, Yunnan, on the southeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. The discovery challenges long-standing views about technological evolution in the region and raises questions about potential Neanderthal dispersal into Southwest China.

The Middle Paleolithic (~300,000–40,000 years ago) was a critical period in human evolution, marked by the coexistence of early modern humans, Denisovans, and Neanderthals, as well as significant technological innovations. Prevailing theories suggest that early hominins in China exhibited slow technological development, particularly in adopting Middle Paleolithic advancements—a notion that has fueled debate over East-West differences in toolmaking evolution.

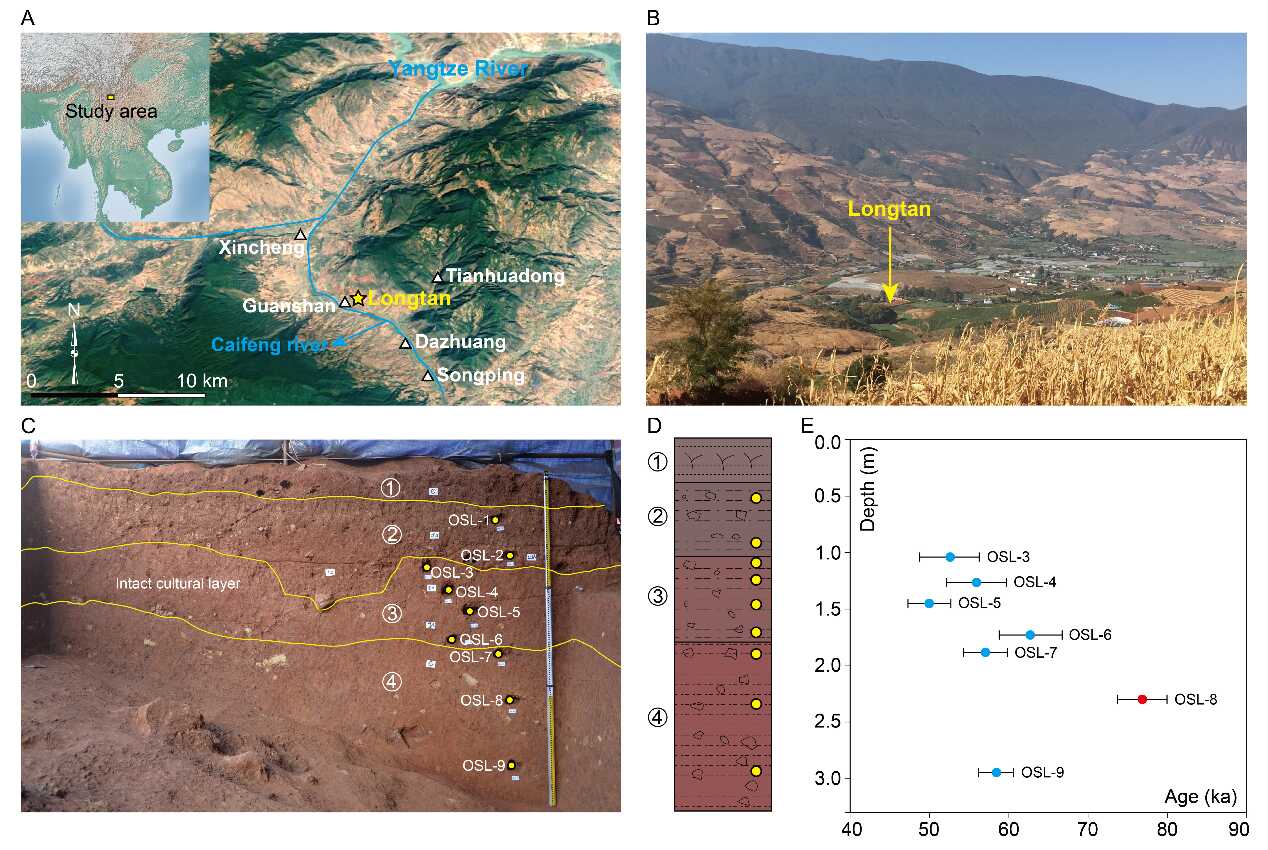

The Longtan site was discovered in 2010 and systematically excavated between 2019 and 2020. Stone tools exhibiting key features of Quina technology—a lithic tradition previously associated with Neanderthals in cold, arid European environments (~70,000–40,000 years ago)—were found at the site. However, the presence of Quina technology in East Asia has never been conclusively confirmed until now, according to co-first author Prof. LI Hao from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research.

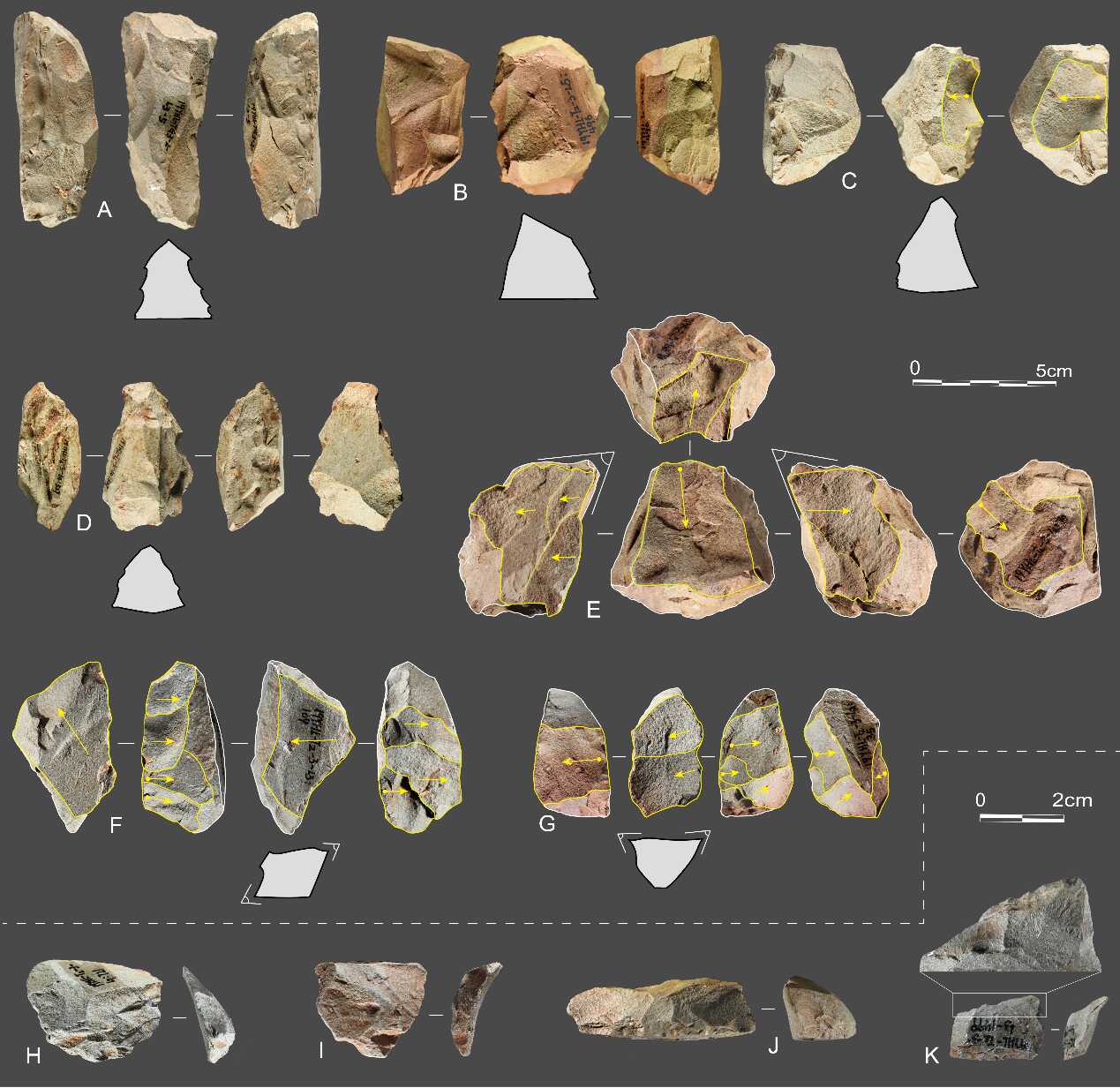

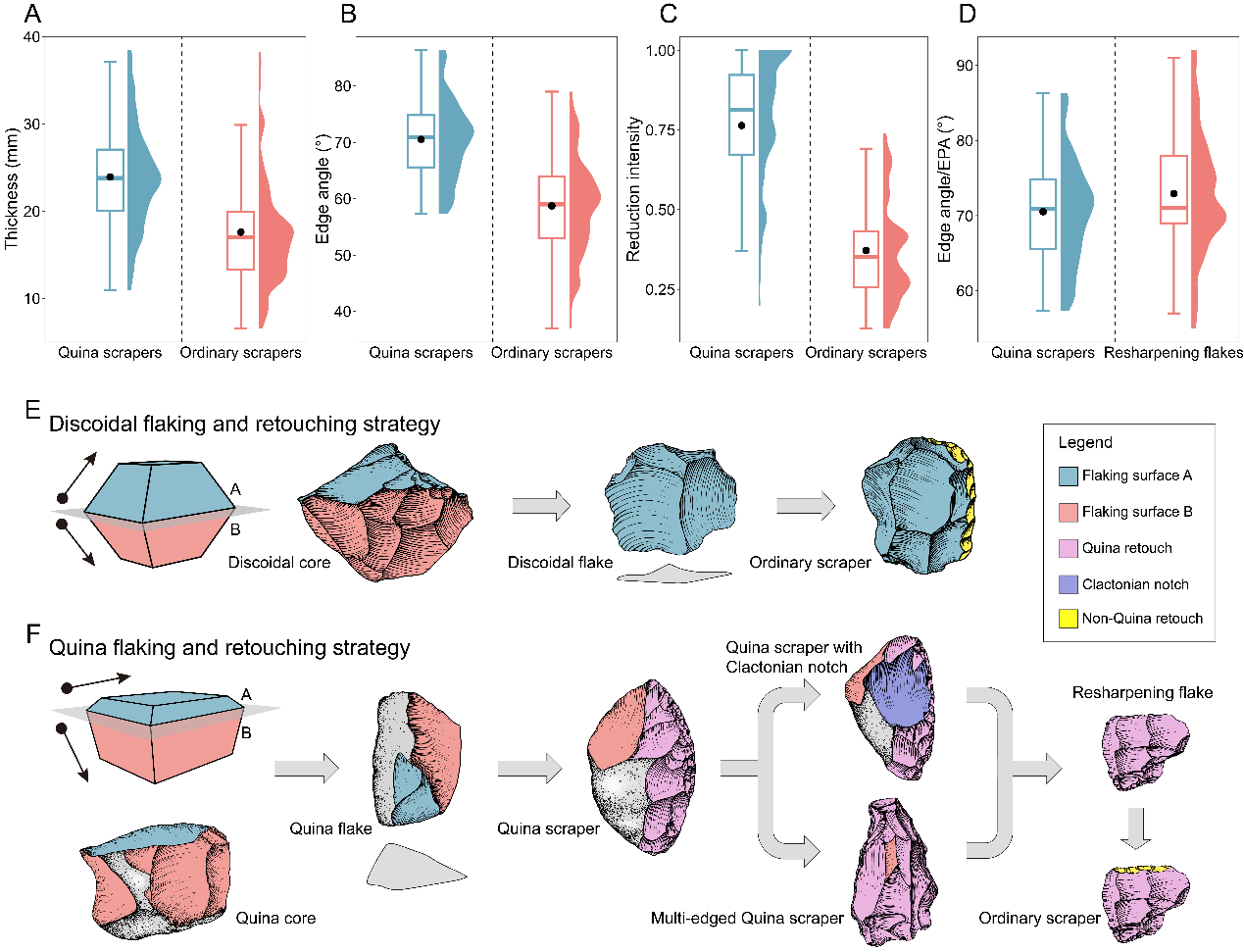

Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating places the Longtan cultural layers at approximately 60,000–50,000 years old, with pollen analysis suggesting the inhabitants occupied an open forest-grassland mosaic environment. In this research, the lithic assemblage exhibits classic Quina technological traits, including the systematic production of thick flakes as tool blanks; selective edge retouching using both soft and hard hammers to create alternating convex and concave scars; continuous edge rejuvenation to extend tool use-life; and the use of resharpening flakes to make small-sized tools. Micro-wear analysis also confirms that Quina scrapers were utilized for processing bone, wood, and hides, highlighting their functional versatility.

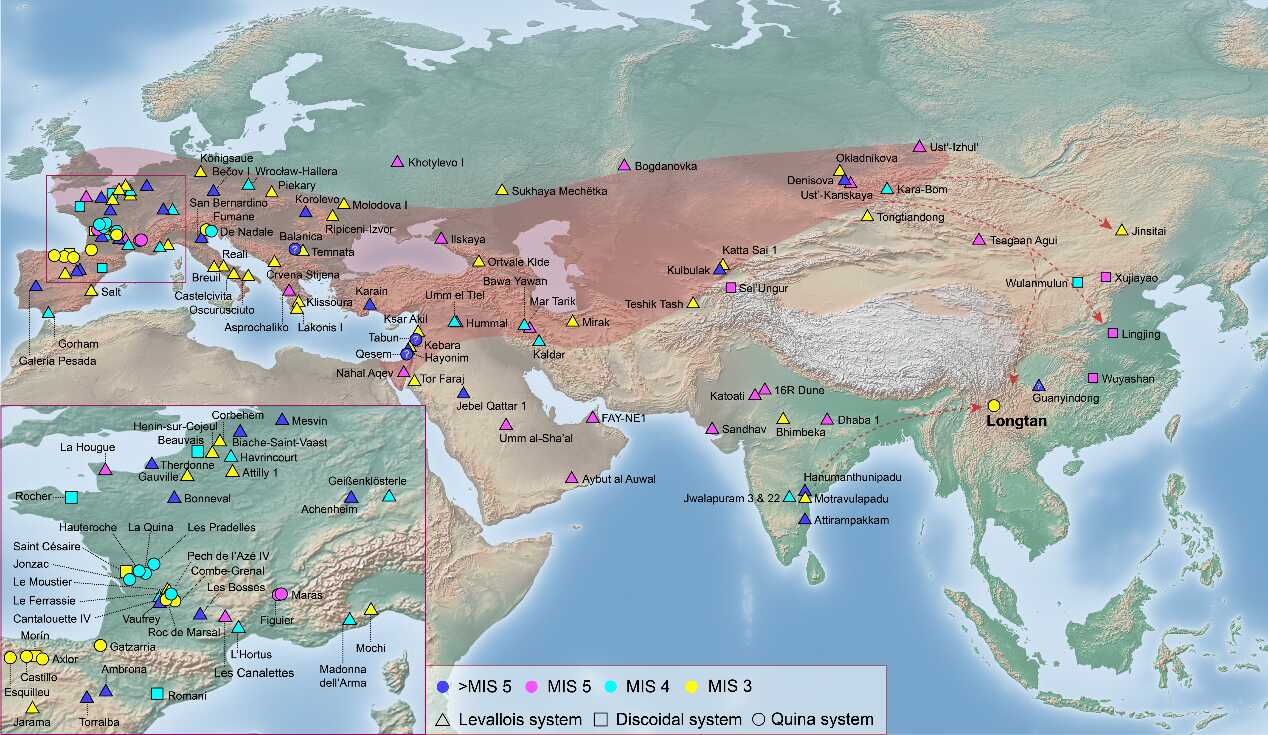

This discovery adds to a growing body of evidence revealing diverse Middle Paleolithic technologies across China, including Levallois techniques dating to approximately 50,000 years ago in Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia; discoidal core technology from around 125,000–90,000 years ago at the Xuchang hominin site in Central China; and Levallois methods spanning 170,000–80,000 years ago at Guizhou’s Guanyindong Cave.

“The Longtan Quina technology reshapes our understanding of East Asia’s evolutionary landscape,” said lead author Prof. RUAN Qijun, a visiting professor at CAS and director of the Department of Paleoanthropology at the Yunnan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. He emphasized that after 300,000 years ago, multiple hominin groups—including Xiahe Denisovans, Homo longi (“Dragon Man”), large-brained Homo juluensis (e.g., Xuchang and Xujiayao populations), and an unknown handaxe-using group—likely coexisted, creating a complex mosaic of regional adaptations.

In Western Eurasia, Quina technology is firmly linked to Neanderthals. Now its confirmed presence at Longtan not only extends the spatiotemporal range of this technocomplex but also raises the possibility of a Neanderthal presence in Southwest China.